For centuries, Isfahan has been a leading hub for Khatamkari experts who breathe new life into objects with intricate inlays.

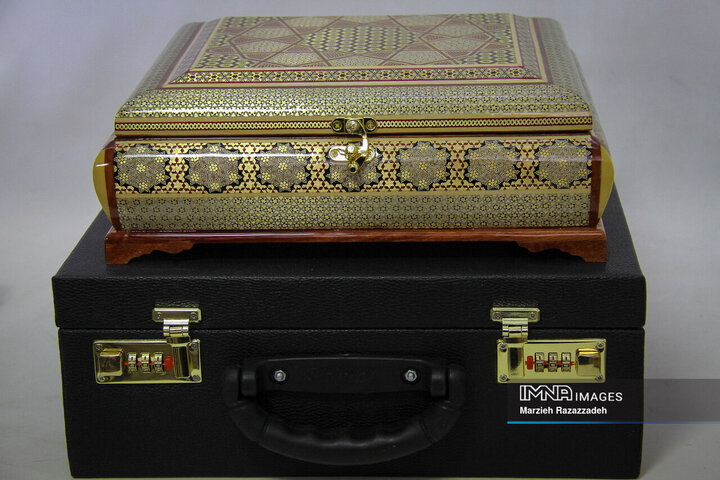

Iran (IMNA) - Marquetry artisans decorate the surface with tiny sticks made of wood, twisted wire, gold, silver, brass, aluminum, or organic materials like shells, mother-of-pearl, and camel bones.

Usually, the sticks are glued together in triangular beams to form a cylinder. The cross-section now resembles a six-branched star and is divided into sections that are one millimeter wide before being cut, compressed, and dried between two wooden plates.

The artisan either drew the pattern on the base wood directly or adhered a paper pattern to the wood in order to achieve the desired result.

Due to the tendency of marquetry work to splinter, exposed areas like keyholes and the edges of designs were frequently covered with intricate mounts made of bronze or other metals to protect them from damage.

Iran has long been home to this form of art. Some outstanding examples are preserved in museums or can be seen in old mosques, palaces, and mansions.

Available evidence such as an ancient minbar (pulpit) adorned with marquetry patterns in the Jameh Mosque of Atigh suggests that the process became popular in Shiraz a thousand years ago.

Narratives say that the expertise found its way to Isfahan in the late 16th century when the economy began to grow and consequently demand for opulent domestic furniture arose.

The Safavid period saw the use of Khatamkari on a variety of objects, including doors, windows, mirror frames, Quran boxes, pens and penholders, and lanterns, lending it a special significance.

Over time, inlay masters have tried their best to preserve the nobility of the ancient craft, and at the same time, they have tried to introduce novel ideas to keep art lovers fascinated.

Your Comment