Iran (IMNA) - Parental economic deprivation, lack of access to inclusive education, being misplaced and refugee, growing up in dysfunctional families, living with addicted parents and states' inadequate laws and regulations are the main determinants behind the global phenomenon of child labour.

The International Labour Organization (ILO) defines child labour as “work that is mentally, physically, socially or morally dangerous and harmful to children; and/or interferes with their schooling by: depriving them of the opportunity to attend school; obliging them to leave school prematurely; or requiring them to attempt to combine school attendance with excessively long and heavy work” (ILO, n.d).

Grappling with forced labour is part of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, adopted by global leaders in 2015. An agenda through which all countries pledged to achieve 17 sustainable goals and 169 specific targets toward a promising future for all, which are collectively titled the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Target 8.7 of the Sustainable Development Goals focuses on “immediate and effective measures to eradicate forced labour, end modern slavery and human trafficking and secure the prohibition and elimination of the worst forms of child labour.”

The Goal Target 8.7 would not be obtained unless global leaders redouble threir efforts. Eradicating child labour requires integrated thinking, coordinated actions, effective policy making and efficient use of resources in unprecedented ways.

All endeavors and coordinated actions must address the underlying causes of the modern slavery, and help discover the right incentives and deterrents to make change for a peaceful world.

Realizing SDG 8.7 will require the effective engagement of partnership of all parts of societies including governments, NGOs, employers' associations, private and public sectors, educational bodies, community organizations, faith-based organization (FBOs) , and media agencies .

In 2024, the global fight against child labor saw both progress and persistent challenges as efforts to address this critical issue continued. Despite earlier commitments, including the United Nations' declaration of 2021 as the International Year for the Elimination of Child Labour, the situation remained dire for millions of children worldwide.

The child labour problem is not unique to poor or war-torn countries; rather, it is an important issue in most developing countries like Iran. The country has long been involving in eradication of the child labour.

"Figures released by the Iranian Ministry of Cooperatives, Labor, and Social Welfare in 2017, indicated that there were 500 thousand underage laborers in the country that were classified into 3 categories: street vendors, waste pickers, and children working in factories," Mahmoud Aligoo, the head of Iran's Center for Social Emergency Medicine, said in a national TV show titled "Gheir-e Mahramane" focused on *Street and Working Children*.

He went on to say that, "The number of street-connected children is not clear; however, according to the latest reports by Iranian non-governmental organizations (NGOs), there are nearly 4,000 children in Tehran scavenging on rubbish dumps [in search of scrap metal and plastic to sell them to recycling dealers.]"

"The majority of the underage laborers falls into the category of "children working in factories" which has received the slightest attention. Counting the population of the street children is not possible; however, based on the State Welfare Organization’s report, it is estimated that there are about 14 thousand working and street children all over the country. The number of waste picker children is less than the other two categories and considered as one of the unusual and dangerous types of occupations. According to information released by Iranian non-governmental organizations (NGOs), there are about 4,000 underage waste scavengers in Tehran," he noted.

Aligoo added, "Regarding underage scavengers, it can be stated with certainty that most of them are foreign nationals and immigrants from Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. There is also no available information on the spatial distribution of the street children.”

In most low-income Iranian families, elder boys have the primary responsibility for feeding their siblings; However, it is not uncommon to see girls, particularly those from Afghan families, working in activities such as incense burning, selling goods, or shining shoes.

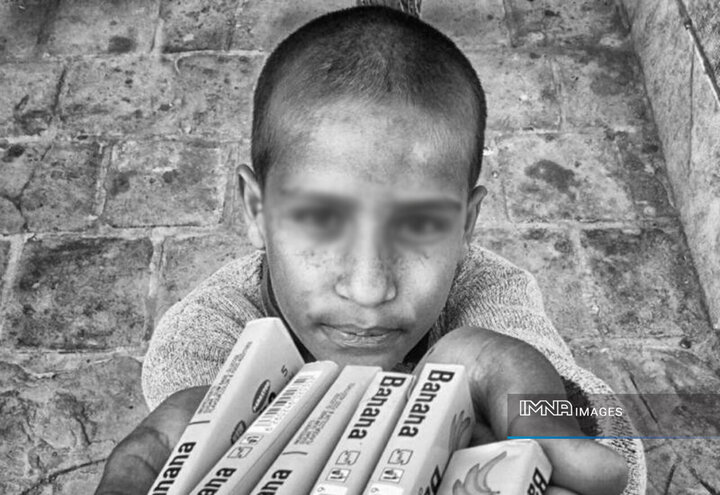

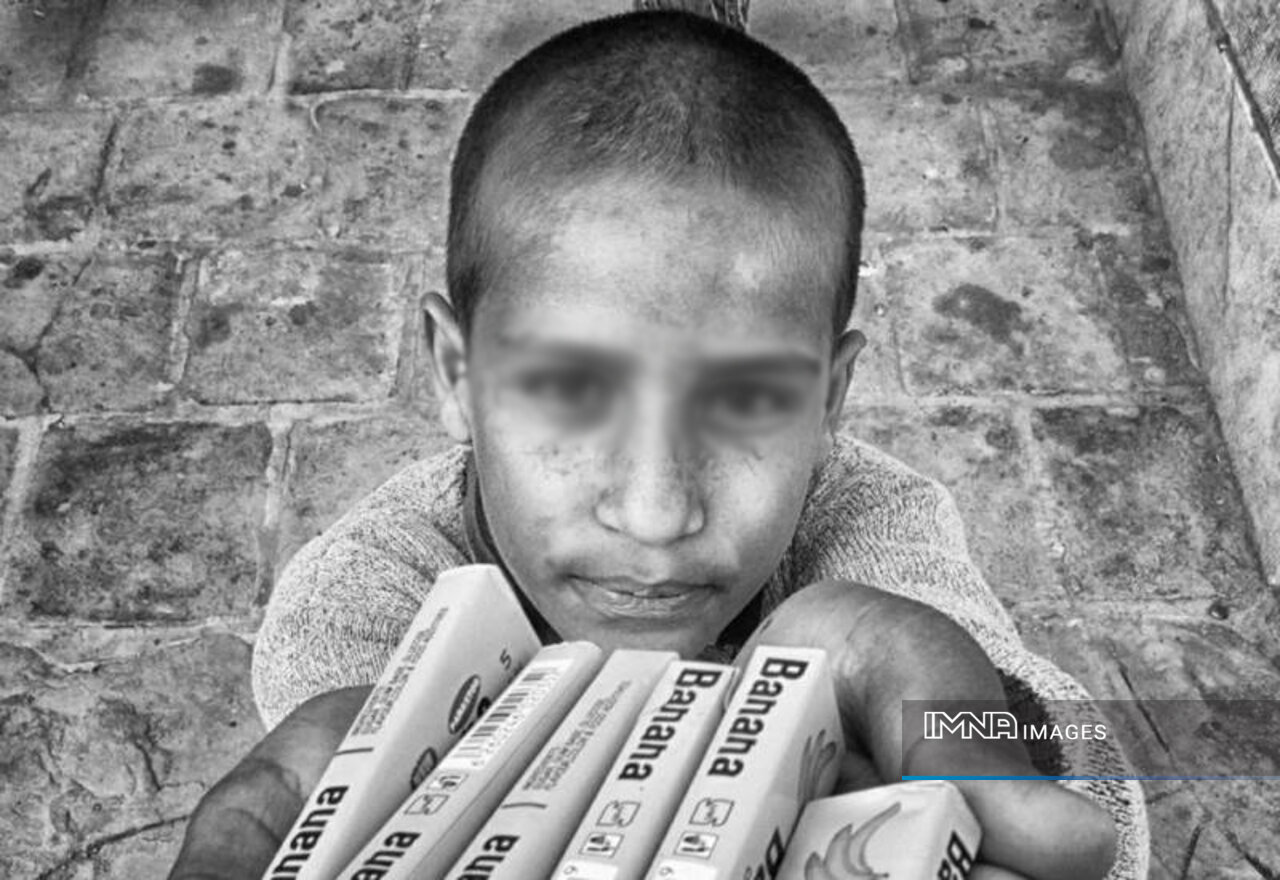

Forced to work on streets, Ehsan and his younger brother Omid, have been vending and picking waste in Tehran’s streets for the last four years.

They are working on streets simply because their father has lost his job and there is no money to feed the family.

“Four years ago, our father fell from a construction site where he was setting up scaffolding, " Ehsan told IMNA. “His spinal cord was injured, and the damned thing about it is that he was not covered by occupational accident insurance.”

Their father, who also suffered brain damage due to exposure to the blast wave, is a victim of the Iran-Iraq War with neurological and psychological injuries and is experiencing worsening conditions. This is largely due to his prolonged and excessive use of strong psychiatric medications.

His illness deteriorates daily, often reaching a point where he screams loudly from midnight until morning. It's terrifying for them as they fear he might harm himself. Their hearts ache for him because they believe he's innocent—it was the war that brought this suffering upon him.

Iranian war victims frequently grapple with post-traumatic stress disorder, a condition characterized by negative thoughts, depression, attention problems, anxiety, and hypervigilance. These symptoms can manifest years after the traumatic event, affecting not only the individual but also their family and relationships.

This condition often co-occurs with other mental health issues such as depression, anxiety disorders, and substance abuse, creating a complex web of challenges that require comprehensive support.

Witnessing their father's struggles with his condition has been a deeply emotional experience for the two brothers. Despite their desire to provide supportive care and a nurturing environment, they face a significant challenge: they lack the knowledge to offer the proper care he needs. In an effort to compensate for his disability and support their family, the brothers have taken to working on the streets.

The two boys are the breadwinners and responsible for their three little sisters. Despite receiving social welfare assistance from Iranian supportive organizations, they still face difficultie. Their daily income ranges between 200 to 300 thousand Toman with which they can only buy some foodstuffs on the way back home.

Ehsan and Omid are unable to attend schools everyday due to the need for making more money to sustain their family.

“Every day we walk about six kilometers to get to our place of work. Our biggest wish is to go to school on a daily basis because we enjoy studying,” Ehsan said.

"I like playing football with my friends rather than being on streets in this baking heat," Omid continued.

Ehsan, the elder brother, looked at Omid pityingly and sighed, “I hope my father recuperates soon and gets a high-paying job at the earliest possible time so that we could get rid of street vending.”

The plight of children like Ehsan and his younger brother Omid highlights the harsh realities faced by many families. Behind the considerable numbers are individual children, each with wishes and aspirations for the future. Under the slogan “Take steps to eliminate child labour”, Iranian authorities are committing to undertake targeted adaptation actions that prepare the grounds to end child labour; However, ordinary people should also notice that they take a huge role in effective abolition of child labour.

Many people are still unmindful of the impact of child labour which is a gross injustice facing millions of children. To encourage as many people as possible help to end this global phenomenon, it is important to show how we are all connected to the challenge; we should bear in mind that everybody can assume a role even if very little.

Let’s continue providing children with life-saving helps and expand the circle of cooperation. Ask ourselves and each other – what more is needed to ensure there’s no children left behind in our own countries and communities?